Saya yakin anda akan bersetuju muzik yang memainkan peranan penting dalam filem . Skor muzik yang baik membantu memindahkan cerita, mencipta ghairah dan memancing emosi. Seram, ketegangan dan filem thriller memanfaatkan kekuatan muzik untuk membina pendahuluan penampilan dan takutkan adegan tertentu. Berikut adalah beberapa skor paling menakutkan yang pernah ditulis untuk filem-filem seram.

Carrie - Berdasarkan novel karya Stephen King,filem ini tentang seorang gadis remaja yang mempunyai kuasa telekinetic, salah satu kegemaran saya. Pino Donaggio menulis skor untuk filem ini, yang paling terkenal adalah "School in Flames."

Jaws - Tema utama filem ini tahun 1975, yang mungkin menakutkan setiap pengunjung pantai bagi sesiapa yang pernah menonton filem ini. Skor lagu bagi filem ini dicipta oleh John Williams. Selalunya orang akan mengunakan atau mengajuk lagu tema filem ini ketika anda sedang di pantai. Williams meraih Academy Award untuk skor filem yang tetap menjadi salah satu tema filem yang paling dikenali sehingga saat ini.

Halloween - John Carpenter, Pakar bagi filem "keganasan," mengarahkan filem seram ini pada 1978 tentang pesakit jiwa bernama Michael Myers melarikan diri. Carpenter sendiri menulis skor untuk filem ini yang dilaporkan mengaut $ 75.000.000 di seluruh dunia yang pada asalnya hanya mempunyai kewangan hanya $ 300,000.

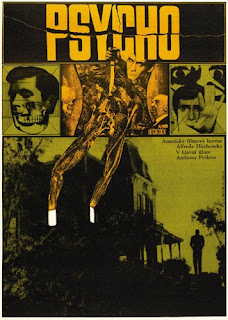

Psycho - Filem 1960 diarahkan oleh Alfred Hitchcock legenda dan berdasarkan novel Robert Bloch. Adegan paling terkenal dan tak dapat dilupakan adalah pada babak lagi "shower scene." Ganas dari adegan yang diperbesar oleh skor yang luar biasa Bernard Herrmann's.

Rosemary's Baby - Tema utama dari filem 1968 dicipta oleh Krzysztof Komeda. Muzik boleh digambarkan sebagai pengantar tidur dengan undertones sinis, sebuah perlawanan yang sempurna untuk plot filem. Tema daripada "Rosemary's Baby" selalu membawakan perasaan menakutkan, bahkan sebelum mempunyai kesempatan untuk menonton filem ini.

The Exorcist - 1973 Lagu berjudul "tubular Bells" yang ditulis oleh Mike Oldfield. Muzik itu sendiri adalah tidak menakutkan berbanding dengan nilai lain. Tapi yang digunakan dalam filem, muzik berubah menjadi salah satu nilai yang paling mengerikan untuk sebuah filem seram.

The Omen - 1976 filem amat menyeramkan, paduan diantara suara Choral dan digital bunyi dahsyat dan menakutkan-terdengar berjudul "Ave Satani." skor ini ditulis oleh Jerry Goldsmith yang meraih Academy Award untuk sumbangannya kepada skor muzik layar perak. Banyak versi dari "Ave Satani" telah tercatat sejak pertama kali keluar, tetapi versi asal tetap kegemaran.

The Sixth Sense - ketegangan menakutkan ini menyentuh tentang seorang anak yang "melihat orang mati" keluar pada tahun 1999. Nilai indah ini ditulis oleh James Newton Howard dan merupakan campuran dari muzik menyentuh dan pulsa-membesarkan, khususnya "Suicide Ghost," "Hanging Ghosts" and "Kyra's Tape."